The D.C. Intertie: A Lifeline to California and An Engineering Marvel

Golden State Study Highlights Inequities in Roof-Top Solar

August 31, 2020

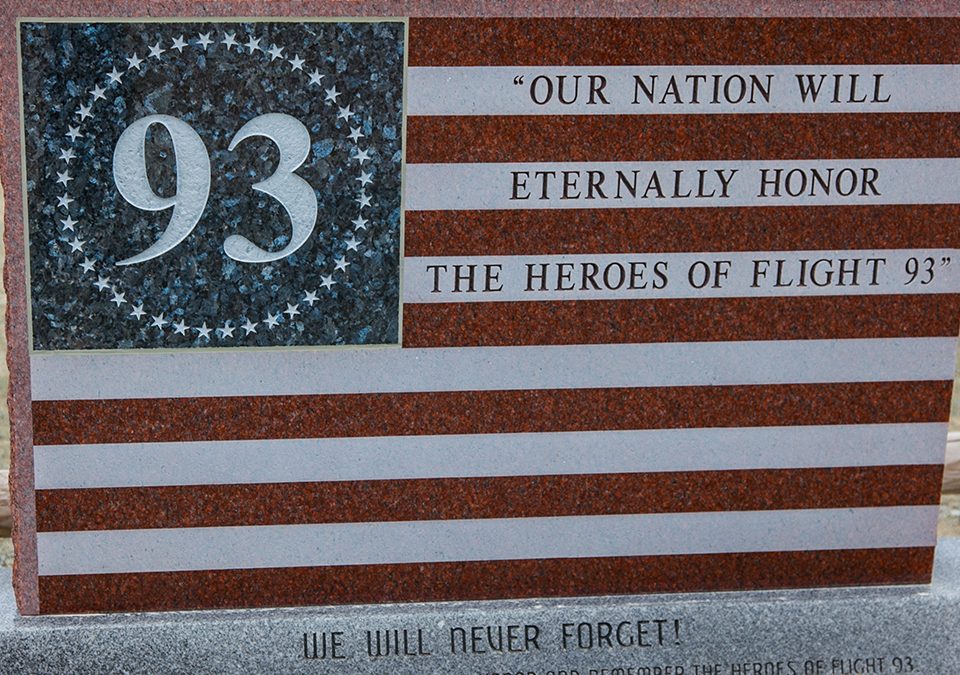

Flight 93: Electric Co-op Heroes on a Day of National Tragedy

September 11, 2020It’s been just over 50 years since Neil Armstrong took man’s first steps on the moon, uttering the memorable phrase – “that’s one small step for man and one giant leap for mankind.” His words put the final stamp on a phenomenal engineering achievement first presented as a challenge to America’s engineering community by President John F. Kennedy during his inauguration address on January 20, 1961.

But while the moon landing was no doubt an engineering marvel, even the iconic Armstrong noted that the development of the electric grid might have surpassed it. When discussing the electric grid in the context of the other top 20 engineering feats, Armstrong stated: “the majority of the top 20 achievements would not have been possible without widespread distribution of electricity…Clearly the ready availability of the electric power we use in our homes and businesses exemplifies how engineering changed the world during the 20th century.”

There’s a strong argument that the development of the electric grid is the greatest engineering accomplishment in human history. Yet, the grid consists of many remarkable engineering marvels that make it run. One of those was the construction of the DC/AC interties – a north-south transmission line network connecting the Pacific Northwest’s vast hydropower resources to the burgeoning demand for affordable and reliable power in southern California.

For its 25th anniversary in 1962, President Kennedy sent the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) a note commending the federal utility for its contribution to the region and nation. In his praise, he said, “When you help your region, you help build your nation…Bonneville’s first 25 years point the way to ever bigger contributions to the economic growth and prosperity and security of our nation.” The President’s words were prescient as plans were in their infancy to connect the Pacific Northwest to the rapidly expanding Southern California economy via a revolutionary new technology known as the D.C. Intertie.

What exactly is the D.C. Intertie? It’s a series of four extra high voltage alternating current (A.C.) and direct current (D.C.) transmission lines. Collectively, they create the largest single electric transmission link in the U.S. The three A.C. lines connect from John Day Dam on the Columbia River in eastern Oregon to points in northern California. The massive D.C. line runs 842 miles over 4,200 towers from Celilo, near The Dalles, Oregon, to Sylmar just outside Los Angeles. The line is jointly owned by BPA and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power with the transfer of ownership occurring on the Oregon/Nevada line.

This series of lines helps maintain an affordable and reliable supply of power to California during times of peak need, as we recently saw during the first weeks of August. Or, as former BPA Administrator Bill Drummond describes the importance of D.C. Intertie, “It serves as a critical lifeline to the Southern California economy during the hot summer months when electricity demand is at its peak.”

The series of A.C. lines connecting the Pacific Northwest to northern California is impressive, but they pale in comparison to the technology developed to build the D.C. intertie. This massive transmission line can deliver up to 3,100 megawatts of affordable, reliable, and renewable hydropower, making it an engineering marvel within a marvel.

To make the D.C. Intertie a reality, BPA engineers had to develop such things as the largest mercury arc converters in the world and implement new computing techniques to embed the direct current line within the overall alternating current network. After nearly 50 years of service, it was, in the words of one BPA executive, “one of the nation’s greatest engineering feats…and ultimately paved the way for future long-distance interties around the world.”

Fast-forward to the severe electricity shortfall that California suffered through last month. It’s easy to see how much worse it could have been had affordable, reliable firm power not been sent down to southern California from the mighty dams on the Columbia through D.C. and A.C. networks.

In fact, in the midst of the crisis on August 16, while California’s grid operator forced surrounding utilities to institute rolling blackouts, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power was able to keep the lights on because “it generates, IMPORTs [D.C. Intertie] and transmits its electricity and was able to meet the city’s demand.” In other words, the D.C. Intertie was a critical lifeline providing affordable, reliable, and renewable hydropower during a time of unrelenting energy demand for customers.

The DC Intertie is indeed an engineering marvel embedded within the world’s greatest engineering feat, our power grid. It’s critical that policymakers acknowledge the importance of infrastructure such as this and continue making the necessary investments to keep them available for the good of customers. We can only have reliable and affordable power if the infrastructure exists to produce and deliver it.

Online recommendations

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Nuovi

- Casino Non Aams

- Slot Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Online Casinos

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- UK Betting Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- New Non Gamstop Casinos No Deposit Bonus

- Casino Non Aams

- Migliori Casino Online

- Crypto Casino

- Meilleurs Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Casino Con Prelievo Visa

- Site De Poker En Ligne Francais

- Meilleur Site De Paris Sportif Hors Arjel

- 出金早いオンラインカジノ

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne

- オンラインカジノサイト

- Casinos En Ligne France

- Bitcoin Casino Italia

- Casino En Ligne